If you’ve ever assigned a personal narrative writing prompt like “Tell me about a time you were brave,” and been met with blank stares, you’re not alone. I remember giving those prompts early in my teaching career, thinking personal narrative writing was the easiest and most natural place to start. After all, students were just writing about their own lives—how hard could that be?

Turns out, personal narrative writing is actually one of the most cognitively demanding tasks we ask of students. Once I understood why, it completely shifted how I approached writing instruction.

Why Personal Narrative Writing is SO Challenging

Personal narrative writing requires students to do a lot of mental heavy lifting. First, they need to recall a very specific memory, often from several months or even years ago. Then, they have to remember small details—what they saw, heard, felt, even what someone said. On top of that, they’re expected to organize it all into a well-structured story with a clear beginning, middle, and end.

That’s a big ask—especially when you consider how tricky memory recall is for many students. Let’s be honest, most of us can’t remember what we had for dinner last Thursday!

Beyond the memory challenges, many students just haven’t had enough structured practice with storytelling. Writing a compelling personal narrative requires more than just sequencing events. It’s about:

- Pacing

- Voice

- Character development

- Story Arching

- Building Tension

When these skills aren’t modeled or practiced regularly, personal narrative writing can end up vague and underdeveloped. Plus, asking students to write about personal topics can actually cause some to shut down. If a student doesn’t feel like they have something interesting or relevant to say, the prompt can lead to frustration instead of engagement.

A Shift in Thinking: Write About What They Know

So, what’s the alternative?

One of the biggest shifts I made in my writing instruction was moving from personal narrative writing to more content-based expository writing. Here’s why: when students are writing about something they’ve been learning in class — say, a science topic like life cycles — they already have the information they need to write confidently.

Instead of asking them to pull from their own (often foggy) memories, you’re giving them a strong foundation of content knowledge through reading, discussions, and direct instruction. Then, you’re asking them to write about what they’ve learned — which makes writing feel a lot more manageable and less intimidating.

For example, after spending a week reading texts and discussing the life cycle of a chicken, students could write an explanatory paragraph about that process. They already know the vocabulary. They’ve seen diagrams. They’ve talked through the stages. Writing becomes an opportunity to communicate what they’ve learned—not a guessing game.

I have had some teachers reach out with worry about copying. This is an inevitable step in learning. Imitation is often the first step to learning. To help your students avoid copying straight from a text or book, you can show them a Model Paragraph — it might be one you have written or found in your curriculum. Even if your students are copying the Model Paragraph to some degree, they are learning how to write complete sentences. They are being exposed to different sentence structures. Once they gain confidence in writing, they will most certainly start adding their own ideas and new details.

Narrative Writing Doesn’t Have to Be Personal

Now, before you worry about standards—yes, narrative writing is still important. But the standard doesn’t say students must write personal stories. It says students should “write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events.” Let’s expand how we define narrative writing.

Narratives can include:

- Summaries of stories students have read

- Biographies of historical figures written in narrative form

- Historical fiction based on real events

- Retellings of content-based stories or processes

The common thread? Students are still using the elements of narrative writing—like sequencing, dialogue, setting, and transitions—but they’re not starting from scratch. They’re applying those skills to content they’ve already explored.

This approach makes writing more accessible. It boosts confidence. And it still allows room for creativity and student voice. Even if 25 students are writing about Harriet Tubman’s rescue missions, no two pieces will be exactly the same. They’ll each reflect unique word choices, organization, and writing style.

One of the biggest benefits of this shift is that when students write about what they’ve read, their comprehension improves too. Research shows that writing about reading strengthens understanding and retention. It’s a win-win: your writing block reinforces your reading instruction.

Try This in Your Classroom

If you’re curious about making this shift, start small. Try building your next writing assignment around a science or social studies topic. After a week of reading and discussing the content, invite students to explain it in writing. You’ll be surprised at how much stronger—and more confident—their writing becomes.

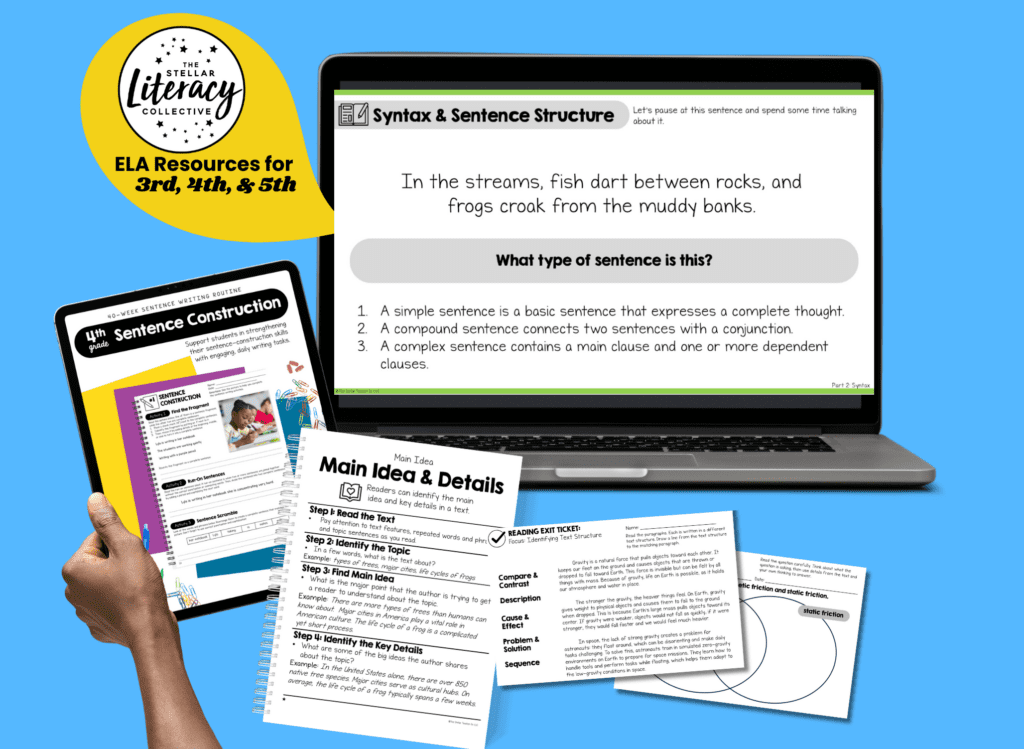

And if you’re looking for support and ready-made resources to make writing instruction easier, The Stellar Literacy Collective can help. Inside the membership, you’ll find content-connected writing lessons, structured routines, and all the tools you need to empower your students as readers and ]writers.

Let’s rethink narrative writing together—and help our students become more capable, confident writers in the process!

Happy writing!

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.